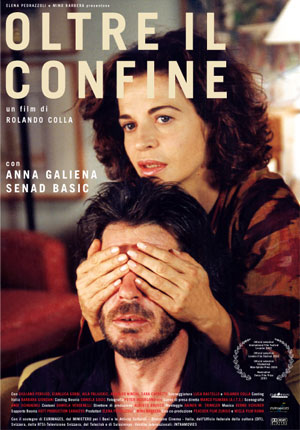

Oltre il Confine

| 2002 |

|

104 min, 35mmby Rolando Colla with Anna Galiena, Senad Basic Original version in Italian Switzerland/Italy |

| Director Statement |

Statement by Director Rolando Colla

I have attempted to tell a true-to-life story. We shot the film at the genuine locations and with a hand-held camera to make it as authentic as possible. The characters from Bosnia are played by Bosnian actors. They experienced the war at first hand. Formally, we refrained from anything showy. I did not want to bluff. I wanted to document something that will soon be forgotten, something that will literally disappear from our view: The houses destroyed in Bosnia are being rebuilt. What will be left to remind us of the devastation that took place in the country? The aging men who were soldiers in WWII are gradually passing away. Agnese’s father, whose funeral is shown in the film, is one of them. What will be left of the experiences from WWII once the eyewitnesses are no longer among us? There is just one war veteran’s home in Italy. A part of the film takes place in this institution and we spent two weeks shooting there shortly after the Italian Army had vacated the premises because there were too few veterans to warrant keeping it open. In that sense, the film also provides a record of both the war in Bosnia and WWII. The protagonist, Agnese, travels to Bosnia where she recollects her post-war childhood years. She had suppressed the memories for many years, just like the victims of war who generally seek to recover from their experiences by locking away the pain deep inside. The repression of this individual and collective pain is possibly a reason why wars happen almost as a perverse matter of course. I am interested in finding a way of expressing this pain, especially the pain trapped inside.

Notes by the Co-Author Luca Rastello When the war broke out in Bosnia, reactions in Italy diverged considerably: On the one hand, there were many spontaneous reactions, solidarity rallies and events, driven by the awareness that the situation had to be addressed without delay. 70,000 Italians set off for ex-Yugoslavia, either to supply relief aid or to organize the reception of refugees. On the other hand, the passive response demonstrated by the official institutions was astonishing: In 1993, a year after the war had started, Italy had officially taken in 11,500 Bosnian refugees (while Croatia had admitted 700,000 and Germany more than 300,000), and the Italian police proudly proclaimed that it had turned back 20,000 refugees at the country’s north-eastern border. Still today, most of the reconstruction work in the Balkans is being done by private organizations with volunteers. At the same time, the government does not tire from conveying the image of the refugee as a threat to Italy. The film tells a story about a single individual in 1993. It also includes elements that should lead the audience to reflect on both the current situation and our future. |

|